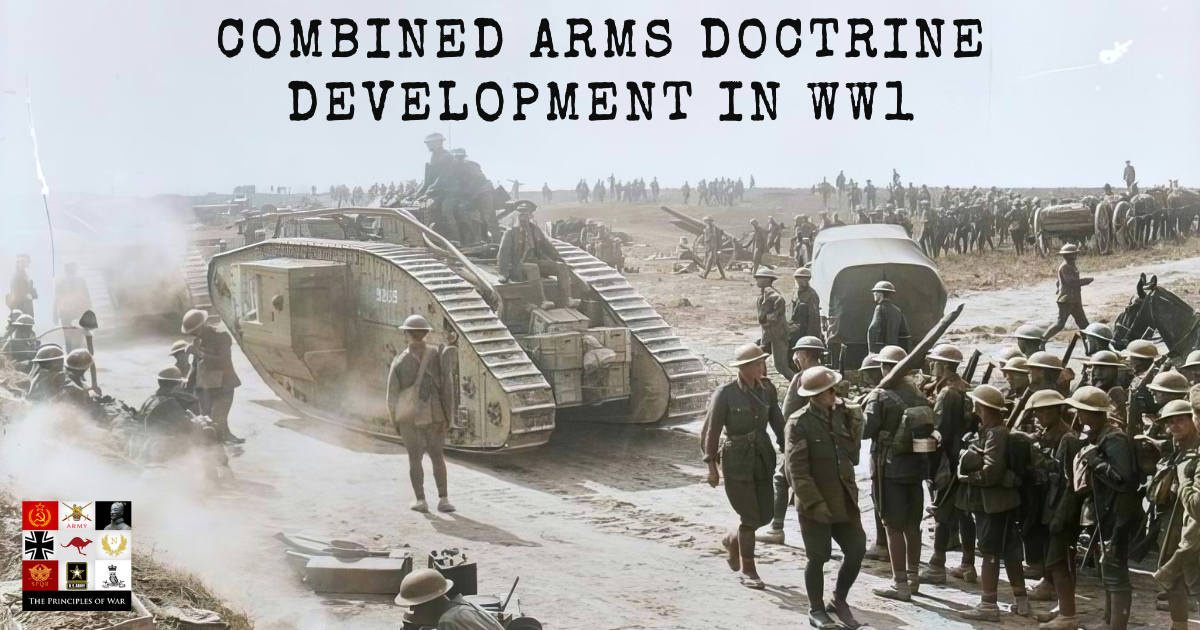

We discuss the lessons learnt from the First World War, in particular for Combined Arms, in the British Army with Dr Robert Lyman, co-author of Victory to Defeat with Lord Richard Dannatt. These are the show notes for the podcast, for all of the details, please listen to the podcast on your favourite podcast player.

In 1918, Britain produced just 91 guns in 1914 and this was scaled up to 1918 in 10,000. Britain had an Army that was focused predominantly on a force structure for wars like the Boer War. Robert discusses why the European Armies ignored the lessons from the US Civil War – such as the difficulties in manoeuvre on the modern battlefield with machine guns and artillery.

The cost of the lessons learnt in the early part of the war was very heavy in both blood and treasure.

A National War

Britain struggled to transition to a National War, as opposed to an expeditionary war. The Asquith Government fell because of the ‘shell crisis’ as Britain worked to transform the national effort to focus on the war effort. The military had to transform to create a modern Army fit for the modern battlefield. This took changes in equipment, doctrine and training.

In the Second World War, the British Army underwent a similar process with the need to update doctrine, equipment and training because of the mobile warfare that the German Army was using. It took the British Army until D-Day for the Commonwealth Armies to be probably equipped and ready to face a modern Army.

If you think about how to fight, you’ve got a better chance to be able to do it. Thinking about how to fight and equipping armies to be able to fight in a war against an enemy and the way that they will fight is critical to success.

Between 1931 and 1940, there was not one formation-level exercise in the British Army. This mistake made

Second El Alamein

Montgomery’s plan for the Battle of Second El Alamein was predominantly a First World War battle with Second World War equipment. This was the first battle that saw the successful generation of the Combined Arms effect. It took so long into the Second World War because logistics, signals and Command and Control capabilities needed to be augmented from their peace time capabilities to those of an Army fighting a large-scale combat operation.

What was the legacy of Second El Alamein for British Army doctrine until the 1980s?

How did the British Army learn to learn?

The Divisional commanders were left to themselves in the way that they fought their battles. The Fourth Corps was very successful by innovating through trial and error, learning from their mistakes and ensuring that lessons were learnt and that the development of combined arms was improved. This was important as Generals looked to integrate the new capability – tanks into their design for combat. Artillery also needed to be integrated into battles in a lot more sophisticated way. Fires were used to shape the enemy for a battle, denying logistics support and denying the enemy the opportunity to use their weapons. The growing sophistication in orchestration and synchronisation created the ability to achieve a breakthrough in the German lines.

All this needed to be done whilst looking at the development in the air domain needed to be integrated as well.

Why was the British Army surprised tactically and doctrinally at the start of the Second World War?

The ability to think and craft a process for generating combat power is a key capability. Compare and contrast the British Army in 1918 with its offensives of the 100 days, with the German ‘Blitzkrieg’ operational manoeuvre developed in the Battle of France and how the British Army was fighting in the first part of the Second World War.

The ability to imagine what the battlefield will be like, what the enemy will be like and how they will fight, and what differences technology will make to the battlefield and combat are critical to ensuring that early battles in the next war are not a debacle.

Between 1931 and 1940, the British Army did not have one formation level (or higher) exercise. These exercises are an important part of testing what will work and what won’t as well as testing and training the troops in all of the requirements for generating combat power. These kinds of manoeuvres also test the command and control that is required to orchestrate and synchronise effects.

We discuss the work of General Sir Ivor Maxse, the British Inspector General of Training and his role in developing doctrine, lessons learnt, pamphlets and training troops for the changes in the battlefield and tactics.

Have a listen to the podcast for this great discussion with Robert and his learnings about doctrinal development in the First World War and how it impacted the Second World War.

4 comments

Very interesting podcast, showing the genesis of combined arms doctrine. It is a shame that the battle of Le Hamel, 4th July, 1918, wasn’t used as one of the first examples of combined modern warfare, utilising all the arm services in an innovative way.

Thank you. The book does mention Hamel, and at some stage we will look at Monash’s masterpiece. It is an excellent example of combined arms, and also innovation with quite a few new techniques being bought onto the battlefied.

Totally agree with the above about the Battle of Hamel as the first example of combined warfare with tanks,artillery and air planes. General Monash had meticulously calculated the duration of the battle and was only out by 3 minutes.

[…] episode continues our discussion with Dr Robert Lyman about British doctrine development in the inter-war period. Robert is a military historian and co-author of Victory to Defeat: The British Army 1918–1940, […]