Combined Arms doctrine lessons learnt and lessons forgotten during the interwar period.

We discuss how the lessons learnt from the First World War, particularly for Combined Arms, in the British Army were forgotten, with Dr Robert Lyman, co-author of Victory to Defeat with Lord Richard Dannatt. These are the show notes for the podcast, for all of the details, please listen to the podcast on your favourite podcast player. This is the second part of the interview. The first episode can be found here.

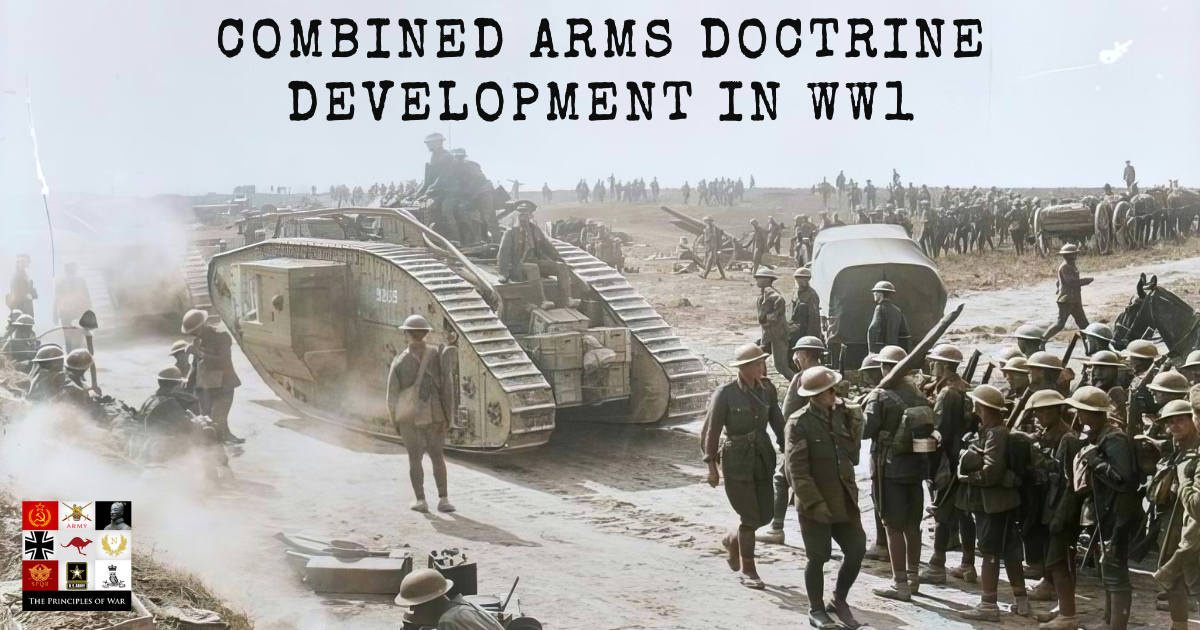

Before the Battle of Hamel. Monash was given freedom to develop a plan for battle without significant constraints enabling a combined arms plan that incorporated considerations for German reactions to the attack to which Monash was able to develop appropriate countermeasures.

We discuss the celebrations for the victories of 1918 that were conducted in 1919 and 1920 and how the view of the War changed over the years to focus on the stalemate in the trenches. The impact of the casualties, the sense of loss throughout society and the impact of the physical and mental wounds that returning soldiers had coloured the way the war was remembered. This is partially why the memory of the victories of the 100 days is blurred.

The old adage that victory is a poor teacher and the Wehrmacht studied and learnt the lessons of the 100-day battles. They were able to innovate their combined arms doctrine through exercises and TEWTs (tactical exercises without troops) at the corps and army levels. This was married to extrapolation of how technology would change the character of war.

We see the depression and the economy, a fear of a new world war, unwillingness to maintain an Army to fight on the continent, a lack of desire to invest in technology as well as no clearly defined grand strategic end state creating a situation that inhibits the British Army’s ability to innovate. There was a strong desire to view the First World War as an outlier in historic events that would never be repeated. There is always a tendency within armies to plan for the ‘proper’ war – the kind of war that they are most comfortable fighting. This fails when enemies are incentivised to fight a war that targets your weaknesses. Without a clear purpose, it was difficult for the Army to articulate how it contributed to a national deterrent when looking for funding from the Government.

How did the state of the British Army impact the ability of the British Government to deter German aggression in 1938 and 1939? An earlier podcast, the British Centre of Gravity under Neville Chamberlain, discussed how a deterrence strategy without a creditable military was unlikely to succeed, especially with a leader like Hitler who was prepared to gamble at the National Strategic level.

How do we enable better decision-making at the Grand Strategic level? Britain had no Minister of Defence with three service chiefs competing against each other, so there was no coordinated military strategy. There was no Grand Strategic plan and that made planning impossible. This was complicated by Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister and the belief that he had in his own strategic insights.

The British Army had an Army of movement, not an Army of manoeuvre and that mistake would be discovered in France in 1940. This raises a key question – how does an Army know if its doctrine is capable of winning?