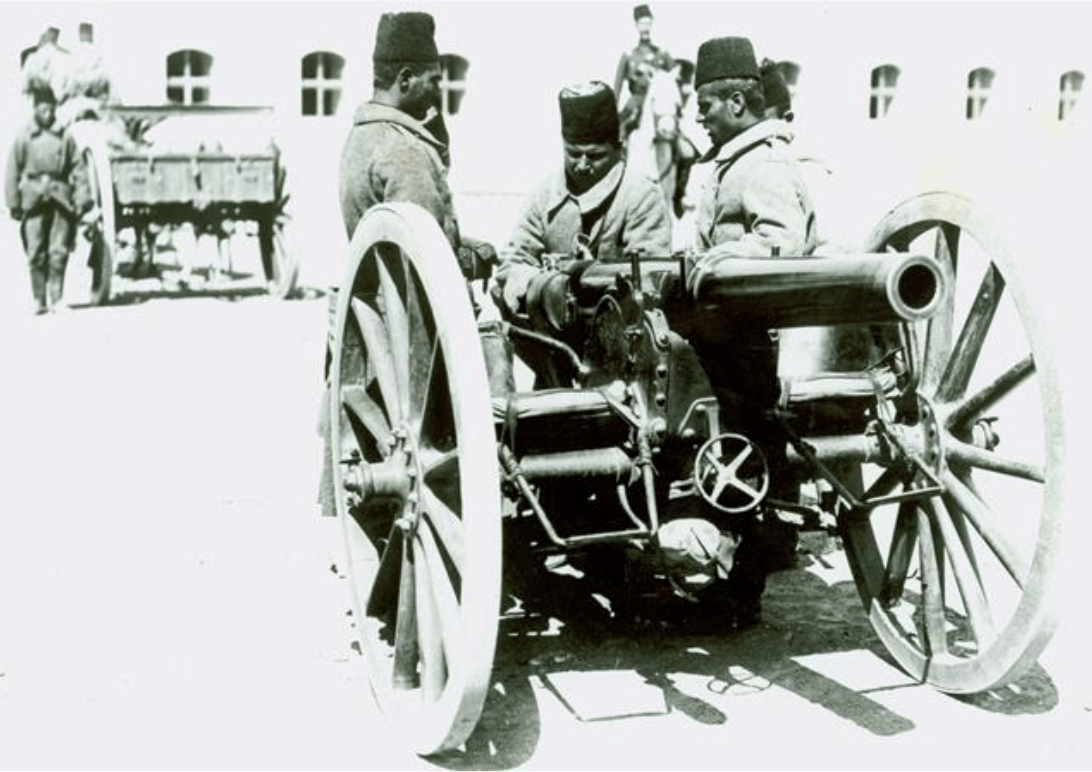

This podcast on the Ottoman Artillery is is the third session of the second seminar in the Royal Australian Artillery Historical Association’s Firepower: Lessons from the Great War Seminar Series. This is presented by Professor Mesut Uyar, a graduate of the Turkish Military Academy with numerous command positions in the Turkish Army, including Battalion Commander. He also has a Ph.D. on International Relations from the Faculty of Political Sciences Istanbul University. He was a lecturer at the UNSW and is currently lecturing at Antalya Bilim University.

These are the Speakers Notes for the presentation on the Ottoman Artillery at Gallipoli.

Organisation of the Ottoman Artillery Corps

Therefore the establishment numbers of batteries and guns had to be reduced and obsolete guns that had been discarded were reintroduced. In 1911 the Ottoman army replaced the well-established square division structure (two brigades each with two regiments) with a division comprising three regiments each with three battalions. This new structure eliminated both brigade headquarters and a regiment.Consequently, the divisional field artillery brigades were transformed into three-battalion artillery regiments. After the Balkan Wars, however, the number of battalions and batteries had to be reduced due to shortages of guns and equipment. According to the new establishment, each divisional field artillery regiment would have two battalions each with two batteries. One battalion would be field artillery equipped with eight 75mm Krupp Feldkanone L/30 M1903and the other would be mountain artillery equipped with eight 75mm KruppGebirgskanone L/14 M1904. Nevertheless, there were not enough guns to equip batteries even according to this lean establishment. To address this shortfall, 87mm Krupp Feldkanone L/24 M1885(better known as mantelliin the Ottoman army),75mm Krupp Gebirgskanoneand some other guns were introduced as replacements. Howitzers and heavy artillery units, generally, were placed under the corps or field army artillery groups. Similarly,a general lack of howitzers and heavy artillery kept these formations weak.

The Dardanelles Straits

The Dardanelles Straits and Gallipoli Peninsula had been part of an organised fortress command from very early times. Throughout this period, defence of the area remained largely the responsibility of the Ottoman artillery corps. In fact, almost every artillery officer, particularly the heavy artillery branch, served at least one term in the Dardanelles Fortified Zone Command (Çanakkale Müstahkem Mevki Kumandanlığı) prior to 1914. This defence arrangement was changed when the WW1 started. First,III Army Corps in Tekirdağ (Rodosto) moved to the Gallipoli Peninsula to carry out the defence against amphibious landings on 2 November 1914 and the Fifth Army was activated under the command of LTGEN Liman von Sanders (a German officer) and took over the defence responsibility on 26 March 1915.

The Ottoman Fifth Army in comparison to other field armies was lucky. Not only İstanbul, the main production and transportation hub, was near but also the Dardanelles was part of Fortified Zone Command. That means there were various mobile batteries in the theatre already. During the initial landings on 25 April 1915, the Ottomans quickly learned that naval gunfire was ineffective against entrenched units. After the initial landings more and more batteries from the Fortified Zone Command were transferred to Fifth Army. Although most of these borrowed batteries were deployed to the Southern Group (Helles) –due to the close proximity to the Strait fortifications -this gave an opportunity to Liman von Sanders, commanding general, to station his organic army and corps artillery troops to the Northern Group. Between 25 April and 20 May, Liman von Sanders and the Ottoman High Command expected to repulse the Allied troops from their fragile beachheads. When a series of large scale Ottoman counterattacks and following Allied attacks failed miserably, the ensuing stalemate turned into trench warfare. The Ottoman artillery played critical roles during attacks and counterattacks but most of the structural changes took place after 20 May.

Ferik (LTGEN) Esad Pasha was assigned as the commander of the Northern Group with four divisions (5th, 9th, 16thand 19th). The deployment of the Northern Group just before the August Offensive was, from north to south: the 19thDivision (all four regiments at the front), 16thDivision (all four regiments at the front) and 9thDivision (one regiment at the front other two regiments in reserve). The 5thDivision (two regiments) was corps reserve. The Suvla region was covered by two independent detachments which were Anafartalar Detachment (four battalions) to the north and Ağıldere Detachment (14thRegiment). Both of them put weak screening forces at the coastline and kept strong reserves. Due to terrain, previous experiences and availability of non-organic artillery reinforcement, Esad Pasha changed the composition of the artillery unit drastically. He assigned batteries with modern field guns to divisional artillery regiments (enhancing their mobility)and positioned batteries armed with old or heavy guns at specific fixed positions. These (fixed) batteries were given under the tactical command of the division which was responsible for that sector but they were to remain in their positions regardless of the rotation of the divisions. His corps artillery commander was tasked to carry out coordination and supply of ammunition. Division commanders and their artillery regiment commanders remained in charge of their sectors. Most of the artillery batteries were positioned at Gun Ridge (Topçular Sırtı).

In conclusion, the Ottomans protected their guns well by digging and preparing well-fortified and concealed positions with alternatives to be used when necessary. Lacking the necessary resources and technical means to break the deadlock, the British army and allies at this stage had no answer for an enemy in good defensive positions. Essentially to crack open the Ottoman fortifications and well-protected gunnery positions, the British and allied artillery should have adopted siege tactics and techniques. This would have meant more heavy guns –especially howitzers-, more suitable ammunition types and large quantities of ammunition and a methodical approach. Unable to get more and better guns the British, however, had no choice but to use shrapnel in an attempt to suppress the Ottoman guns.

Join the conversation on Twitter or Facebook.

If you’ve learnt something from today’s podcast, please leave a review for the Podcast on your podcast player.