Who was deceiving who in the Winter of 1950? We look at Chinese deception tactics, self-deception and the Magruder principle on the Yalu River.

These are the show notes for our episode looking at Chinese deception tactics in the Korean War, please listen to the podcast episode for the whole story on your favourite podcast plater.

To Surprise is to Conquer. Marshall Suvorov.

This episode looks at how the US was surprised twice, firstly by the DPRK invading South Korea and how the Chinese deception tactics surprised the US on the Yalu River.

References:

Weaving a tangled web. (This is an excellent resource).

FM 3-13 Army support to Military Deception

ATP 7-100.3 Chinese Tactics US Army analysis of likely PLA tactics

Stratagem – Deception and Surprise in War, Barton Whaley

Stunning intelligence failures, the rigidity of mind and excellent Chinese tactical camouflage led to a stunning reversal of fortunes for the UN forces in late 1950 on the Yalu River.

On the 27th of September, 2 days after the Inchon landing, the NSC sent Memorandum 81/1, reminding McArthur that operations north of the 38th Parallel were only authorised if there was no risk of Chinese intervention.

The UN forces crossed the 38th Parallel on the 1st of October.

Mao wrote in 1938 in On a Protracted War, “These two things, creating illusions for the enemy and springing surprise attacks on him – are used to make the enemy face the uncertainties of war while securing for ourselves the greatest possible certainty of gaining superiority, initiative, and victory.” This is an excellent description of what was driving Chinese deception tactics in 1950.

By the time the UN forces reach the Yalu River, the Chinese had 24 out of 39 in position, waiting to cross the Yalu.

Marshall Peng took command of the Chinese People’s Volunteers, a ruse to give plausible deniability that China was not intervening in the war. Marshall Peng was one of the most experienced commanders in the PLA. In his ‘Memoirs of a Chinese Marshall’, he wrote,

“The US occupation of Korea, separated from China by only a river, would threaten Northeast China. Its control of Taiwan posed a threat to Shanghai and East China. The US could find a pretext at any time to launch a war of aggression against China. The tiger wanted to eat human beings; when it would do so would depend on its appetite. No concession could stop it. If the US wanted to invade China, we had to resist its aggression. Without going to a test of strength with US imperialism to see who was stronger, it would be difficult to build socialism. If the US was bent on war against China, it would want a war of quick decision, while we would wage a protracted war, it would fight regular warfare, and we would employ the kind of warfare we had used against the Japanese invaders.”

Willoughby, MacArthur’s Intelligence Officer filtered out the tactical intelligence of the build-up of Chinese troops, including interviews with captured Chinese prisoners who spoke about the intentions of the CPV to intervene in against the UN forces.

SLA Marshall wrote in the River and the Gauntlet,

‘In the hour of its defeat, the Eighth Army was a wholly modern force technologically, sprung from a nation which prides itself on being as well informed as any of the world’s people. The Chinese Communist Army was a peasant body composed in the main of illiterates. Much of its means for getting the word around was highly primitive. In recent centuries, its people had displayed no great skill and less hardihood in war. But they matured their battle plan and become the victors on the field of Chongchon because they had a decisive superiority in information.’

This information superiority is the key to the success of the CPV intervention. It resonates with the changes in reversal of information superiority that occurred during Operation Bertram at 2nd El Alamein where Rommel lost his key information source from a spy in Cairo as Montgomery received Ultra decryptions.

MacArthur, interestingly, never spent a night in Korea – one can’t help but think that this lead to his very poor situational awareness.

Largest single vessel NEO (Non-combatant evacuation operation)

The SS Meredith Victory conducted an evacuation with 14,000 civilians on board. The ship was designed to carry just 12 passengers. Over 100 000 troops required evacuation, many streaming south from the Chosin Reservoir. Civilians flocked to the port of Hungnam for the opportunity to be evacuated. The ship is credited with the largest single vessel non-combatant evacuation operation. Five babies were born during the passage of the SS Meredith Victory. This operation was conducted during the bitterly cold Korean winter and civilians were packed like sardines within the cargo holds and on the deck, many with just standing room.

The Captain, Leonard LaRue wrote later of the evacuation,

‘I think often of that voyage. I think of how such a small vessel was able to hold so many persons and surmount endless perils without harm to a soul. And, as I think, the clear, unmistakable message comes to me that on that Christmastide, in the bleak and bitter waters off the shores of Korea, God’s own hand was at the helm of my ship.’

We discuss all of these and more.

A fascinating look at Chinese military deception and American intelligence failings.

Transcripts

Just who was deceiving who? In the winter of 1950 in North Korea, we look at deception, self deception and the Magruder Principle as China crosses the yalu river in October 1950.

This is the Principles of War podcast, professional military education for junior officers and senior NCOs.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to episode 92 of the Principles of War podcast. Today we’re continuing our studies of deception, following on from our look at oppbertram, the deception plan in support of Montgomery’s attack out at Second El Alamein. We’re going from the hot and flat deserts of Libya to the cold mountainous terrain of North Korea. We moving forward in time. Almost eight years exactly. We’re going to be looking at the period October, November 1950. Very different terrain, two very different generals who’ll be fighting in this battle. And critically, two very different ways of fighting. Marshal Suvarov in the 18th century wrote that to surprise is to conquer. And indeed, Rear Admiral Ella, who was the director of Naval history, was, wrote that it was a surprising war in a surprising place at a surprising time.

Now, if we look at the principle of war, strike the enemy at a time or place or in a manner for which he is unprepared. The North Koreans and Chinese scored the trifecta there. We’re going to be looking at how the United States was surprised not once but twice. Firstly by the DPRK as they attacked South Korea initially, and then by the Chinese as they joined the conflict to support the North Korean government. This is a really interesting case study because the Chinese achieved complete surprise despite messaging that they were likely to attack. Whilst normally you would seek alignment from the strategic down to the operational and then to the tactical level in planning in general and deception planning in particular, this didn’t occur for reasons that we’ll go into operationally.

The PLA was able to move hundreds of thousands of troops to the Korean border and conceal it totally from the United States. We’re going to look at how they were able to do that. We’ll start off by looking at the timeline of the events as they unfolded. We’re then going to look at what were the factors that led to this happening. We look at the Magruder principle and finally we’ll look at some lessons for today, partially in deception planning, but also in how we can minimise the chances of us being deceived ourselves. References for this, we’ve got the Tao of Deception by Ralph Sawyer. Understanding Sun Tzu on the Art of War by Robert Cantrell. Weaving a tangled web. We’re going to be looking at chapter nine, Chinese deception and the 1950 intervention in the Korean War by Joseph Babb.

If you haven’t looked at Weaving a Tangled Web, I’ll put a link in the show notes. Definitely have a look at this. This is part of the Large Scale Combat Operations series by the US Army University Press. It’s a free download and the whole series is really interesting to read. The Military Deception volume is an excellent primer on deception planning. There’s 12 chapters in there looking at 12 different campaigns. One well worth a read. Then we’ll finish off with a little bit of doctrine. We’ve got US Army’s ATP 7 bar 100.3 Chinese tactics. For something a little bit more conventional, We’ve also got FM3.13.4 army support to Military Deception. And finally we’ve got Barton Whaley’s Stratagem, Deception and Surprise in War. We’ll pick up the story. In October 1949, Mao Zedong announces the formation of the People’s Republic of China.

In that same year, the Nationalists retreat to Taiwan. Eight months later we see the North Korean invasion of South Korea that occurs on 25 June 1950. The North Koreans were able to effect almost complete surprise on the South Koreans and their United States allies. Some of the measures that they took to support security and enable surprise were that they had cleared their border regions back to 22 kilometres. Any civilians living in that area was moved out. Between the 15th and 24th of June, the Korean People’s army moved into that zone, utilising it as a forming up area for the assault that was about to occur. These movements though, were detected by the United States and the South Koreans. The United States, the United nations and South Korea all recognised that this was a very precarious border situation.

They’d been subjected to months of not only propaganda but also border raids. What is puzzling though, is that no one was able to correctly divine the North Korean intentions. This is despite the fact that KMag, the Korean Military Assistance Group, which was US advisors to the South Korean government, they had issued a warning stating that an invasion would come sometime in June. That warning was completely ignored. Rather than increasing surveillance and intelligence gathering and looking to build a set of indicators of North Korean intent, nothing was done. Now, the dprk, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the North Koreans, they did do one simple ruse to aid in the deception planning. At the strategic level. They started diplomatic overtures with the intent offering peace proposals for a single national election. They also halted the border raids.

It’s highly likely that this was to offset the fears that the increase in troops on the borders would have engendered within the United States and the South Korean governments and facilitate operational surprise as their troops cross the border. Whaley, in his book, describes the situation as. In sum, then, while the South Korean and American intelligence services and the political military decision makers had more or less correctly assessed North Korean capabilities, they grossly miscalculated their intentions. Thus, when the invasion came in the small hours of 25 June 1950, the South Koreans and Americans were thoroughly surprised by the very fact as well as the timing of the event. Having achieved complete surprise, the Korean People’s army was able to make spectacular gains.

This regional instability so close to the Chinese border, unsettled the Chinese and Mao established the Northeast Border Defence army in July of 1950. This initially saw the movement of four Chinese armies to the border region. Now, back then, a Chinese army was the equivalent of a US corps. Within just two months, the UN forces are bottled up in the Busan perimeter. However, on the 25th of September, MacArthur, in a stroke of genius, conducts a landing at Incheon. Incheon, on the western coast of South Korea and just 25 kilometres from Seoul, offers MacArthur the opportunity to cut the lines of communication with the Korean People’s army that is much further south. Now it is the turn of the KPA to conduct a headlong withdrawal, if not routine. MacArthur is keen to destroy all of the DPRK forces.

He plans another amphibious landing, this time on the eastern side of the Korean peninsula. However, the collapse of the DPRK forces and the rapid advance of UN forces mean that by the time the troops are landed, the port is already in Allied hands. However, by late September, after conducting a series of force marches at night, Chinese Marshal Peng Dihui had assembled over a quarter of a million troops on the northern side of the Yalu River. Further troops continued to pour into the area. These troop movements were hidden from prying eyes by the ttps of the People’s Liberation Army. They would march for almost all of the night, using the last couple of hours before dawn to enable them to conduct cover and concealment so that any aerial reconnaissance would be unable to detect their presence.

During the day, reconnaissance would be conducted of the route and the location of the next night’s staging area on the 27th of September. So just two days after the Inchon landing, the National Security council sent memorandum 811 from Truman to MacArthur, reminding him that operations north of the 38th parallel were authorised. Only if at the time of such operation there was no entry into North Korea by major Soviet or Chinese Communist forces, no announcements of intended entry, nor a threat to counter our operations militarily. I think this is an important piece of the puzzle because MacArthur, with his penchant for offensive action was, will be penalised if he reports any risk of Chinese intervention. And in fact he’s incentivised not to even look for the risk of Chinese intervention.

29 September sees Syngman Rhee’s government, the South Korean government, restored, so MacArthur’s on a roll. Importantly, the very next day, on 30 September, the US defence secretary, George Marshall, sends an eyes only communication to MacArthur. We want you to feel unhampered tactically and strategically to proceed north of the 38th parallel. So importantly, it’s not just MacArthur who’s maintaining this offensive spirit. Now, admittedly his superiors will have been relying off intelligence that will have been coming up from his 8th Army. However, they would have also had access to strategic intelligence feeds above the 8th Army. So clearly, whilst there’s a disconnect intelligence processing within 8th army, there is also a disconnect at the higher level as well. On 2 October, the Indian government had sent a message to the United nations in New York, a warning that they had received from the Chinese government.

This warning came from the Chinese Foreign Minister, Zhao Wen. Lai Zhou’s a fairly important character in this time in the People’s Republic of China. During the war against Japan, he’d been Mao’s liaison with the Nationalists and their US advisors in Chungking. And after the Japanese surrender he’d worked closely with General George Marshall. He’s now the Secretary of Defence. He had sent the telegram to MacArthur saying that he wanted him to feel unhampered and tactically and strategically to proceed north of the 38th parallel. The message that Zhao had sent was unambiguous. If UN forces crossed the 38th parallel and invaded North Korea, China would have to respond to protect itself and its ally.

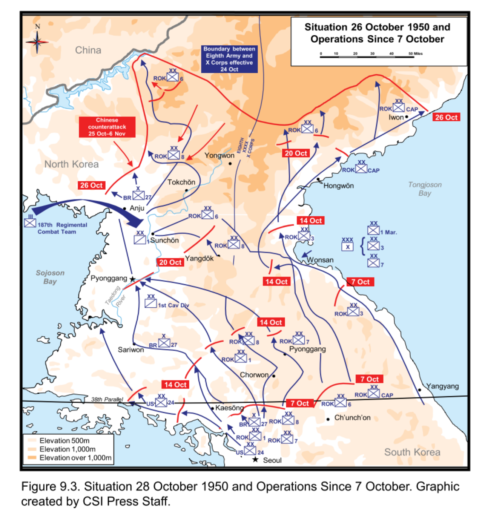

But looking at it from the United States side, by mid October they had crossed the 38th parallel, they had taken Pyongyang, they were within the vicinity of the Yalu river, and this was taken to be an indication that the Chinese were not going to intervene. This, though, is an example of the bias that was being exhibited by decision makers at all levels of the UN and United States command. This bias was playing into the hands of the Chinese deception planning. The big question now for MacArthur is whether the 38th parallel represents a tripwire for Chinese intervention into the war. The advance up the Korean peninsula is made up of UN forces. On the west is the US 8th army and in the east is the South Korean Army. The South Korean army cross over the 38th parallel on the 1st of October.

It isn’t until the 9th of October that the US 8th army crosses the 38th parallel. On the 15th of October, Truman meets MacArthur. Now, Truman’s been President for five and a half years, yet this is the first time that he meets MacArthur. This meeting is quite controversial because MacArthur gets the president to come to meet him on Wake Island. MacArthur is asked by Truman what are the chances of Chinese or Soviet intervention in the war. MacArthur says had they intervened in the first or second month, it would have been decisive. We are no longer fearful of their intervention. We no longer stand hat in hand. The Chinese have 300,000 men in Manchuria. Of these, only 100 to 125,000 were situated along the Yalu and only 50 to 60,000 would be able to get across.

MacArthur at this point has only been able to identify one third of the Chinese forces that are waiting to cross the yalu river on 21 October. MacArthur says the war is very definitely coming to an end shortly. However, Mao wrote in 1938 in his book on the protracted war, these two things, creating illusions for the enemy and springing surprise attacks on him, are used to make the enemy face the uncertainties of war while securing for ourselves the greatest possible certainty of gaining superiority, initiative, end, victory. By the time UN forces reach the Yalu river, the Chinese have 24 divisions in location out of a planned 39. These divisions are on the northern side of the Yalu river waiting to cross. Babb’s chapter in Weaving a Tangled Web describes the situation more than a study in unpreparedness.

Far east commands Willful self deception stands as the archetype of strategic and operational negligence. The Director of Naval History also wrote, in any case, in this one instance, surprise did not need deception. Communist secrecy and American preconception were sufficient guarantors. On 4 October, Marshal Peng, one of China’s 10 marshals, so the equivalent of a US five star general, had been given command of the forces and allocated to the contingency planning, for if the Chinese were required to intervene in North Korea, these forces would fight as the Chinese People’s Volunteers. This was a ruse to maintain plausible deniability that China hadn’t intervened in the war. Marshal Peng writes in his memoirs, the US occupation of Korea, separated from China by only a river, would threaten Northeast China. Its control of Taiwan posed a threat to Shanghai and East China.

The US could find a pretext at any time to launch a war of aggression against China. The tiger wanted to eat human beings. When it would do so would depend on its appetite. No concession could stop it. If the Chinese wanted to invade China, we had to resist its aggression without going to a test of strength with US imperialism to see who was stronger. And it would be difficult to build socialism. If the US was bent on warring against China, it would want a war of quick decision. While we would wage a protracted war, it would fight regular warfare and we would employ the kind of warfare we had used against the Japanese invaders.

Marshal Peng was one of the most experienced and competent Chinese generals from either side of the civil war and conflict with Japan, and he had now received his orders to defend the nation’s sovereignty, ideology and future. By mid October, UN forces in some areas had reached the Yalu River. This is the border between China and North Korea. During the advance, prisoners from not only the Korean People’s army, but also the Chinese People’s Volunteers had been taken. These prisoners were interrogated and they gave detailed information and about not only their current locations but also future intentions. Divisional staffs across the front line, so both on the western and eastern flanks of the North Korean peninsula were aware of the presence of Chinese troops in North Korea and their intentions. This information was not passed up to MacArthur.

Willoughby, his intelligence officer, would filter the information out or obfuscate the true meaning of the reports. MacArthur continued to believe that there was no significant action either currently occurring or planned to happen by the Chinese forces. UN forces were still advancing when Chinese forces launched their first offensive on 18 October. SLA Marshall, in his book the river and the Gauntlet, writes in the hour of its defeat, the 8th army was a wholly modern force, technologically sprung from a nation which prides itself on being as well informed as any of the world’s people. The Chinese Communist army was a peasant body composed in the main of illiterates. Much of its means for getting the word around was highly primitive. In recent centuries, its people had displayed no great skill and less hardihood in war.

But they matured their battle plan and became victors on the field of Chongchon. And because they had a decisive superiority information, the fact that the Chinese were able to develop information asymmetry against a technologically advanced United nations force is the start of the mystery of deception on the Yalu River. It raises questions of how this situation was allowed to develop. How can we guard against this occurring in the future and how can we set those conditions and exploit them in the minds of our enemies? Babb, in Weaving the Tangled Web, says that Peng’s attacking army, consisting overwhelming of semi literate but hardy peasants, lacking significant air cover, artillery and armour, won a campaign of movement, manoeuvre and infiltration.

The CPV supported Peng’s deception through the use of superior operational security, an unsurpassed ability to conceal its staging areas and movements, and the discipline of its massed light infantry. Marshal Peng’s scheme of manoeuvre for the defeat of the UN forces was broken into five phases, or as he described them, campaigns. The first was marked by relentless security to provide the surprise required for the crossing of the Yalu River. In his account of the first campaign, he writes, at dusk on the 18th of October 1950, I crossed the Yalu with vanguard units of the Chinese People’s Volunteers. His plan was to move 11 armies across the Yalu river over the first four weeks of the campaign. His 40th army within the first week had fought two major engagements at Unsan and Bukjin. Following those engagements, the 40th army disengaged and disappeared.

Peng wrote, we employed the tactic of purposefully showing ourselves to be weak, increasing the arrogance of the enemy, letting him run amok and luring him deep into our areas. The dominant narrative that Peng was promulgating to MacArthur was that the Chinese were not conducting a full scale invasion, just messaging a warning to the UN. MacArthur by this stage, having received and ignored Xiao Enlai’s diplomatic warning, having received the briefings from the captured Chinese troops within North Korea, and having fought the 40th army in North Korea, continued to attack. By now Peng had six armies in North Korea. However, rather than attack immediately, an operational pause was put in place to allow the other five armies to cross the Yalu. Babb writes that Peng followed his initial attack with a period of seeming inactivity.

CPV forces across the Yalu dispersed, went into hiding and attempted to avoid contact with UN forces. Additional Chinese forces, travelling only at night, continued to cross at multiple locations along the border. They took full advantage of knowing the patterns used by UN air and ground reconnaissance flights and patrols to avoid detection, Peng assessed the situation and prepared for the next more expansive offensive. This would be the second campaign and Peng wrote, the us, British and Puppet, which he means ROK troops were able to withdraw speedily to the Chongchon river and to the Quechon area where they started to throw up defensive works. Our troops did not pursue the enemy because the main enemy forces had not been destroyed, even though we had wiped out six or seven battalions of puppet troops and a small number of American troops.

Another element of Peng’s success comes into play here. He is targeting the ROK forces for a couple of reasons. Firstly, they were weaker, they weren’t as well trained and they weren’t as well equipped. So offensive action against the South Korean troops was more successful. However, that was only part of it. He was exploiting the natural boundaries of between armies and corps, as well as between nations operating in coalition. To what degrees were the Americans and MacArthur, as the commander, able to generate adequate situational awareness and understanding of the entire front? ROK units would have had a better understanding of what was happening on the ground. However, the natural frictions between organisations trying to pass information, particularly when there are language barriers, created a situation that denied MacArthur the intelligence that he required to be able to properly appreciate the situation had he wanted to.

MacArthur’s situational understanding, driven by his desire to achieve a great victory, was becoming increasingly estranged from reality. Thus, MacArthur launches his final offensive right at the time that Peng launches his second campaign. Peng wrote, we sent small units to engage the enemy and lure him to come after these units. It was nearly dusk when the enemy penetrated the Unsan Kusong line, the place we had planned for our counter attack. Then our main forces swept into the enemy’s ranks with the strength of an avalanche. Chinese special forces, dressed as ROK soldiers infiltrated behind the UN lines, collecting intelligence, attacking logistics elements and sowing confusion as to Chinese locations and intentions. On 24 November, MacArthur makes a flying visit to South Korea. He sees the US ambassador there and briefs him that there are only 25,000 Chinese troops in Korea at the time.

By now, the 10 Chinese armies have almost completely crossed the Yalu River. This was a flying visit for MacArthur because he actually never spent one night in Korea. He managed the entire war from Japan that night. On return, he instructed his pilot to fly up over the Yalu river so that he could conduct a personal reconnaissance. This was less about him gaining situational awareness and more about being able to brief the press that he had conducted a personal reconnaissance of the situation. By the 30th of November, both 8th army and 10th Corps were in headlong retreat in an effort to avoid encirclement.

Peng wrote, the battles of the Chongchon river were a major defeat for the 8th army and a mortal blow to the hopes of MacArthur and the others for the reunification of Korea by force of arms, UN forces established defensive positions in an effort to stem the Chinese advances. Peng then commenced the third campaign. This was to be the breakout and pursuit of the retreating UN forces. After very heavy fighting, Peng was able to force a retreat. This includes the famous battle at Chosin Reservoir. And indeed between the 15th and 24th of December, 10th Corps had to be withdrawn from the port of Hungnam in what became known as the Miracle of Christmas.

Not only were the soldiers from the 10th Corps, 1st Marine Division, 3rd Infantry, 7th infantry and 1st Marine Air Wing evacuated, the ROK, 3rd Infantry Division and Capital Division were also evacuated. Along with all of those troops, 98,000 refugees were also evacuated. One of the ships conducting the non combatant evacuation operation was the SS Meredith Victory, a ship that had been built in 1945 designed to carry 12 passengers with a 47 person crew. On 23 December, the Meredith Victory with its Captain Leonard Larue departed hungnam harbour with 14,000 Korean civilians on board. This is the middle of winter in North Korea and it is very cold. People stood shoulder to shoulder in the cargo holds and on the deck with very little food or water. It would be three days later before the evacuees were able to get off the ship.

Captain LaRue wrote later about the trip. I think often of that voyage. I think of how such a small vessel was able to hold so many persons and surmount endless perils without harm to a soul. And as I think the clear unmistakable message comes to me on that Christmastide in the bleak and bitter waters off the shores of Korea, God’s own hand was at the helm of my ship. Indeed, five babies were born. During that three day passage, Chinese troops continued to advance. They retook Pyongyang and then on the 31st of December they crossed the 38th parallel. They continued, they recaptured Seoul, then they crossed the Hangang river and were able to recapture the port of Incheon. The advance would continue to the 37th parallel over the next two and a half years, Peng would conduct the fourth and fifth campaigns.

These were comprised of very expensive in terms of human life attacks and counter attacks back and forth around the 38th parallel. Bab writes, the Chinese People’s Volunteers had successfully defeated the UN forces sent north to reunite the peninsula, liberated North Korean territory and protected China’s sovereignty. The surprise of the KPA attack in June and the one two punch in October and November conducted by the CPV were significantly enabled by American self deception at all levels. We’ll leave the story of deception and self deception on the Yalu river here, and we’ll come back next week to look at just how this situation could develop.

The Principles of War Podcast is brought to you by James Ealing. The show notes for the Principles of War podcast are available at www.the principles of war. For maps, photos and other information that didn’t make it into the podcast, follow us on Facebook or Tweet us at surprisePodcast. If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please leave a review on itunes and tag a mate in one of our episodes. All opinions expressed by individuals are those of those individuals and not of any organisation.

3 comments

[…] by adminJanuary 4, 2023January 4, 202301 Share << Previous Episode […]

Well nothing has been said about what really happened to the Philippines soldiers during the Korean War . While all the Allied Forces retreated at the 38 Parallel Line the Philippines Contingent stayed .

With the move they did we don’t have South Korea by now. It’s been told to me.by my own late Uncle General Reynaldo Mendoza who at that time a Captain and with the late General Fidel Ramos who just a graduated from West Point of USA .

They belong to the Nenita Unit of the Arm Forces of the Philippines .

Insightful post which I enjoy reading.